Good product roadmaps lie at the core of good product management. The evolution of a product tomorrow depends on the effective planning of the product roadmap today. When it comes to smaller companies and teams with a cap on product development resources, carefully planning the roadmap becomes even more critical. After all, a product manager must think like an economist and come up with an efficient plan for what needs to be built for whom, utilizing the scarce development resources optimally.

But planning a balanced roadmap doesn’t come easy. You might put more effort on UX enhancements for few months and under-develop the operations systems, or, you might build a robust operations system only to realize that there are serious user adoption challenges to be resolved first before you can make good use of the system. Attributing careful weightage to all aspects of the product often requires experiential learning, missing few milestones, and learning by burning your fingers in the process. And situations may not respond very kindly to such misses always. One more milestone miss can be one too many, seriously jeopardizing the product adoption and with it, the product manager’s confidence.

A product manager’s need for a balanced approach towards planning product roadmaps can be fulfilled by approaching it in the same way, in which other functional managers approach budget planning and performance management of their teams by using a Balanced Scorecard [1]. A quick understanding of this concept follows.

The Balanced Scorecard

Every organization works towards a vision, and follows a strategy to meet this vision and create value. When an organization plans for the future, the various business functions follow the core strategy and prepare their plans wherein the management proposes targets and allocates budgets (in terms of resources), and executives agree to those targets and budget numbers. At the end of the budget period, the management appraises their team’s performance on the committed targets and thus identifies the new status of the organization in meeting its vision, as well as the areas of further improvement. More often than not, these targets tend to be myopic in nature, revolving only around the financial metrics, like revenue growth, cost reduction and return on assets. While good for quantitative measurement, sole focus on financial aspects tend to create imbalanced growth. Moreover, in distributed organizations with many divisions, such a focus also increases the chances of meeting divisional goals even when they are not beneficial at the organization level.

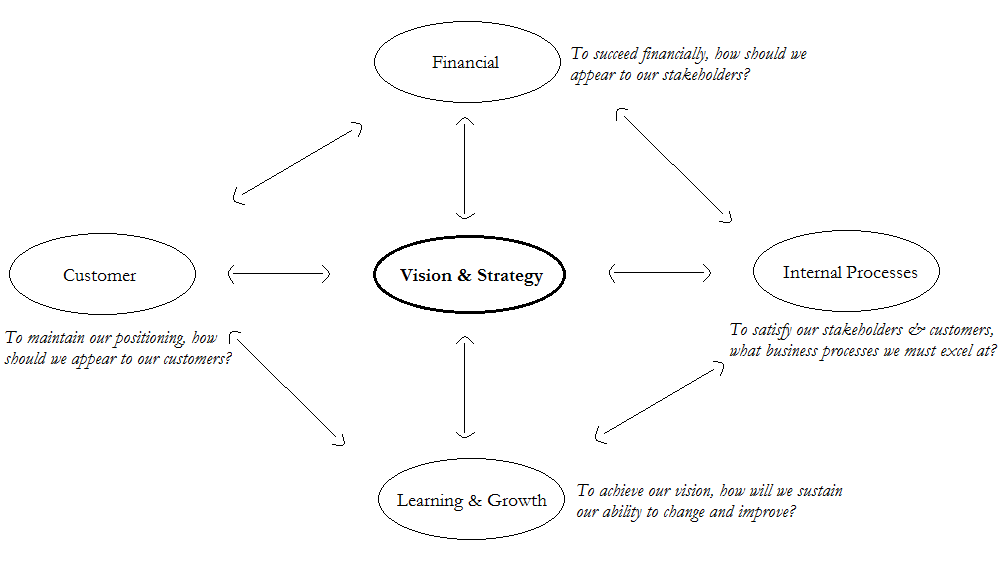

The Balanced Scorecard tries to address this problem by allowing management to focus on more dimensions while strategizing their vision. At its core, it is a management control framework in which the focus is not just on financial perspective while planning and budgeting. In addition, it asks for focusing on 3 more perspectives – Customers, Internal Business Processes, and Learning & Growth.

Using this framework, the management can elaborate their strategy to meet the organization vision across the underlying 4 perspectives. The idea is to identify the core objective for each of these 4 perspectives, and then break that core objective into smaller sub-objectives. Each sub-objective has its own measures, targets, and different initiatives or tasks needed to achieve it. Let’s look deeper.

- Financial Perspective: The core objective here is to find out how should we appear to our stakeholders as a viable business. So the sub-objectives can be to reduce cost, or to optimize utilization of assets, or to define investment strategy to innovate or to create more uniqueness of products.

- Customer Perspective: The core objective here is to find out how should we appear to our target customers, reinforcing the product positioning. So the sub-objectives can be to define target segments and to define value proposition for target customers, or to acquire new customers while retaining the existing ones.

- Internal Processes Perspective: The core objective here is to find out what business processes we must excel at in order to meet our vision. So the sub-objectives can be to identify critical business processes in innovation, operations, sales or customer relationship management. This perspective should have the bulk of all sub-objectives (more than half) an organization plans to achieve in a given budget period.

- Learning & Growth Perspective: The core objective here is to find out how we can continue to grow and be adept at handling it. So the sub-objectives can be to acquire and nurture the fundamental skills and knowledge that enables the organization to meet its vision. The nurturing can be among employees, or leadership, or even knowledge management systems.

Once the sub-objectives are in place, having their measures and targets defined, identifying the initiatives or tasks to meet those sub-objectives, puts action into thought. Thus, the Balanced Scorecard framework tries to give more tangible and granular controls to otherwise seemingly intangible and broad organization strategy and vision. While formulating it or assessing it during appraisals, it helps cover multidimensional growth. It helps strategy implementation across the organization and aligns everyone, from top leadership to on ground workers, by breaking it into more controllable processes of:

- translating the vision in clear objectives,

- communicating and linking the vision with each business function, to even each employee’s granular goals,

- planning for resource allocation as per set targets at each employee level,

- enabling constant feedback and learning as the vision is now broken down into sub-objectives and goals,

and most importantly, linking long term vision with short term actions at each business function and employee level.

Strategy Map & Cause-Effect Relationship

Where a Balanced Scorecard really makes a difference is in its ability to present a strategy map of all objectives and sub-objectives, and help understand the cause-effect relationship between various sub-objectives across the 4 perspectives, and thus tie the strategy in a more holistic manner. And this is where it comes across as a very effective approach to create product roadmaps.

The most common issue with ineffective product roadmaps is that they fall short of aligning all the business functions of the product or the company. I.e., they shape the product in an imbalanced way, and fail to keep all the stakeholders aligned and satisfied with product progress. The ill-represented business function needs in the roadmap fails to secure buy-ins from that business team, and the product manager finds herself in a situation with low or no support from that business function to make the product effective. This is where the Balanced Scorecard approach would come in handy.

Breaking the product vision and the underlying strategy into the 4 perspectives will help granularize the roadmap. Then identifying sub-objectives under each perspective will help align with related business functions. E.g., customer perspective objectives will overlap with marketing team’s objectives, while internal business processes objectives will help find support with operations, tech and design teams. Once all the sub-objectives, and their corresponding initiatives and tasks are defined, the complete strategy map helps put everything under the bigger picture of vision and strategy, and helps tie the long term plan with immediate action items. This helps align not only the business functions, but even the senior leadership.

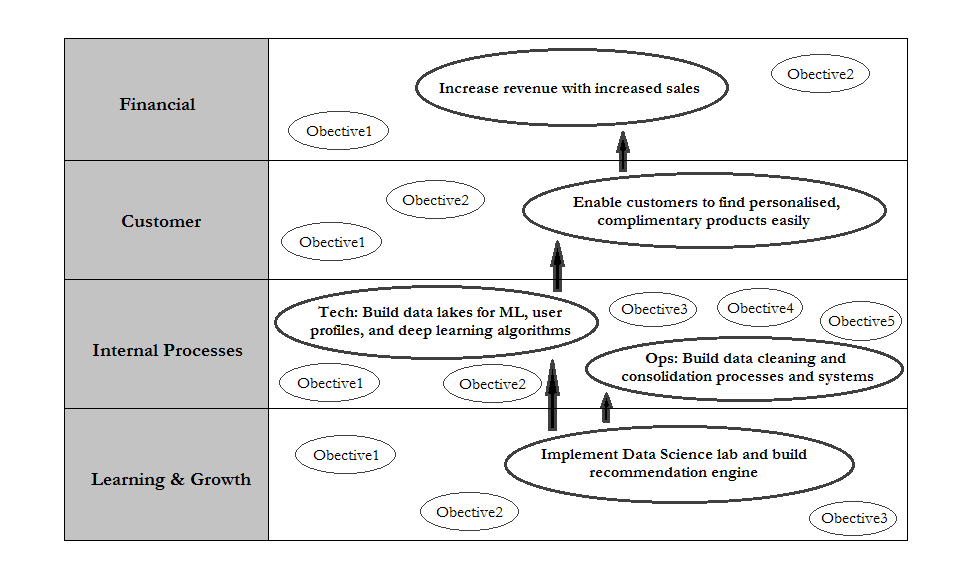

As an example, let’s say a product manager needs to plan for personalization features on, say, an eCommerce product. A lot needs to be built under the hood for such a tech intensive feature, and lack of immediate tangible outcomes tend to alienate the business functions from such a feature. Approaching this feature in the Balanced Scorecard manner might help here. Given below is a strategy map of objectives under the 4 perspectives which ties the cause-effect relationships between the objectives. Such a map might help aligning all the involved business functions.

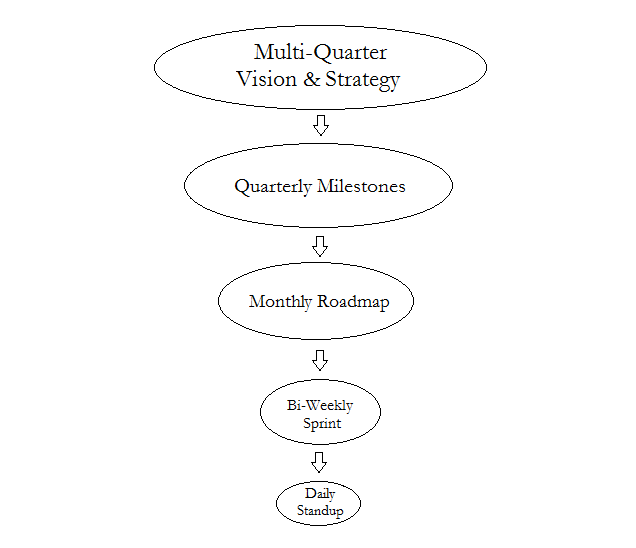

The final approach to share in this post is about tracking the tasks thus identified in a Balanced Scorecard manner. This will differ from one organization to the next, as it depends on the maturity and the scale of the organization. Having said that, a typical such tracker can be the one where the vision and strategy is defined for a few quarters. In such a case, once the sub-objectives have been defined across the 4 perspectives, and the cause-effect relationship among them is clear, the product manager should identify the quarterly milestones for key objectives and their measures. Once all the stakeholders are aligned with these milestones, then the roadmap can be freezed on a per-month basis, picking the tasks which will take the product to the desired milestones. Going further granular and agile in this approach, the monthly roadmap can then be planned as bi-weekly task sprints, where the status is discussed on a daily basis in daily standups.

Exploring the Balanced Scorecard approach and the resulting strategy map depicting cause-effect relationship among product tasks or sub-objectives, will surely help a product manager in many ways. It will not only help create balanced product roadmaps, but also help align all the different business functions with product vision. Most importantly, it will make the product manager think more holistically about the product and its future growth.

[1] The Balanced Scorecard is a strategy implementation and performance management framework which helps align long term strategy with short term actions. It also helps align financial strategies and measures with non-financial ones. It was formulated in the year 1992 by Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, after years of research across industries.